It was hailed as the Great American Eclipse of 2017 and, for the tens of millions of people who gathered along a 70-mile wide strip of the continental United States from Oregon to South Carolina on Aug. 21, it proved to be the experience of a lifetime.

Some called August’s total eclipse of the sun perhaps the most viewed astronomical event in the history of this country.

It was hailed as the Great American Eclipse of 2017 and, for the tens of millions of people who gathered along a 70-mile wide strip of the continental United States from Oregon to South Carolina on Aug. 21, it proved to be the experience of a lifetime.

Some called August’s total eclipse of the sun perhaps the most viewed astronomical event in the history of this country.

The path of totality, as the moon’s shadow crossed the surface of the earth, cut a swath across parts of 14 states: Oregon, Idaho, Wyoming, Montana, Nebraska, Kansas, Iowa, Missouri, Illinois, Kentucky, Tennessee, Georgia, North Carolina and South Carolina.

A partial eclipse of the sun was visible from just about everywhere in North America, including San Diego County where 58 percent of the sun’s disc was hidden by the moon.

For those fortunate enough to view the celestial event that created sensational headlines across the country with dire predictions of food and gas shortages, it was an event not to be missed.

In an amazing coincidence, two former classmates at West Hills High School happened to view the total eclipse from the same campsite in eastern Oregon. They recognized each other just minutes before totality as they lined up to view the sun through a telescope that another intrepid traveler from San Diego County had set up.

Oregon seemed to be the preferred destination for eclipse chasers from California.

“My Dad had read about this and thought it would be a good place to view it, so we came up,” explained Violet Rose, a 2008 graduate of the Santee school. “It’s a once-in-a-lifetime experience. I’ve always been interested in space. I feel connected to the universe.”

Kelly Twichel, a 2009 West Hills High School graduate, remembered Rose from high school. They chuckled about the chance meeting at the remote site in John Day, Ore., a town of about 1,800 located near the intersection of U.S. Routes 26 and 395.

“I never would have imagined that someone I went to high school with would end up by chance in the same tiny spot,” Twichel explained.

Neither Rose nor Twichel were disappointed after making the long trek to the Beaver State.

As the moment of totality neared, temperatures began to noticeably drop and light levels diminished. An eerie brownish glow permeated the surroundings as shadows began to evaporate.

Then, when the moon’s disc completely blotted out the sun, darkness came. It was sudden, as if someone had turned off the light switch in a room.

The moment everyone had been waiting for finally arrived, and eclipse-chasers began clapping their hands and cheering. For many, especially those who had never witnessed a total solar eclipse in person, it was an awe-inspiring event.

For some, it even provided a life-changing experience.

“You have to be there, you can’t describe something so beautiful and impressive,” Twichel said. “It’s the moment science and enjoyment come together.”

Twichel snapped some impressive photos of the eclipse, including the famous diamond ring effect that occurs a second or two before and after totality is achieved.

“It looked awesome,” Rose said, not really needing to add any words.

The two Santee women were among a group of about 150 visitors who gathered on the football field at Grant Union Junior/Senior High School to observe the Aug. 21 total solar eclipse.

The school, with a total enrollment of 200 students, had opened its athletic field to overnight campers wishing the view the event. The $100 camping fee served as a fund-raiser for the school and its athletic department.

Besides having a safe place to camp overnight, the school made restrooms and locker room showers available to campers. Palomar College astronomy professor James Pesavento, who traveled from San Diego to John Day to view the event, was courteous enough to provide a solar eclipse presentation to campers prior to eclipse day.

The school also provided a taco feast to campers the night before the eclipse as part of the fundraiser.

With rumors of some landowners along the eclipse path charging hundreds of dollars for overnight camping privileges or daytime viewing plots, the school came to the rescue of anxious travelers with a win-win situation.

School administrators were excited about the opportunity to host the eclipse fund-raiser, as were the overnight campers who benefitted from the arrangement.

The school made 60 spaces available for guests.

“It’s a great opportunity,” school principal Ryan Gerry explained. “John Day is one of the premier destinations. We wanted to fill the needs to people coming in. We hope we’ve been a good host to those people. We thank them for visiting our school.”

Lights out

As crowds from urban areas flocked to areas inside the blackout zone, there were fears of gasoline and food shortages due to panic buying.

Five million visitors were expected to descend on Oregon to catch a first glimpse of the total eclipse. The city of Madras, with a population of about 6,200, received an estimated 100,000 visitors.

Traffic snarls were commonplace, especially after totality as motorists crowded along highways to get home.

A 25-mile line-up of vehicles was reported heading out of Madras, for instance. It took four hours to travel 26 miles to nearby Redmond – a distance usually covered in 31 minutes.

The National Guard was called out in some states to help maintain order, especially in regard to traffic control.

Gas stations along the eclipse path limited purchases to 10 gallons; customers could purchase two bags of ice.

As one drew closer to the line of maximum totality, signs along the side of the highway offered emergency fuel, food and, of course, eclipse glasses for sale.

Temporary tent cities sprang up on the lawns of private citizens as well as local schools and colleges. Seemingly every available parking spot was occupied in cities that fell under the moon’s sweeping shadow.

Perhaps not surprisingly, price gouging became rampant in some places.

Some intrepid roadside vendors sold eclipse glasses for $50. Children sold lemonade and home-baked cookies from makeshift roadside stands. It was evident that enterprising local citizens cleaned up financially during the event.

In some cases, the sheer volume of visitors was enough to send cash registers into hyper drive. Motels displayed no vacancy signs and restaurants turned back customers due to lack of table space. Some shopkeepers reported they made as much money in one day as they did all summer.

There was one more perhaps even more important factor to ponder: travelers had to hope the weather cooperated in their favor.

Depending on where one was located along the eclipse path, the sun went dark either in morning skies for viewers in the western United States or in the afternoon for viewers on the East Coast.

The maximum duration of totality was two minutes, 40 seconds at any point in the United States. Viewers in the Pacific Northwest got to see a little over two minutes of totality (2:02 in John Day).

While many observers waited in earnest to snap photographs and even view the event through telescopes, some travelers simply wanted to take in the celestial event at a more sublime level, opting for eclipse glasses rather than additional optical aid.

No one seemed disappointed.

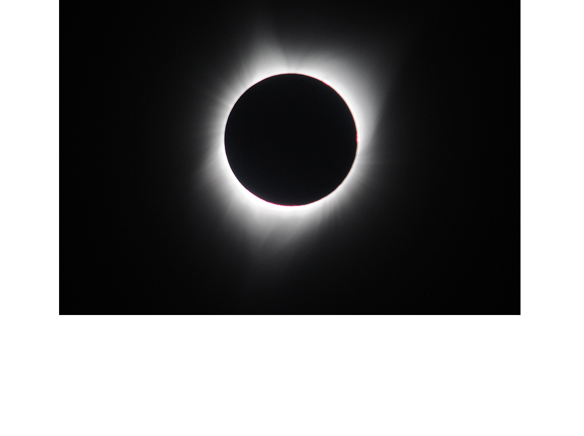

It is during totality that the sun’s tenuous outer atmosphere, the solar corona, is visible to the unaided eye. It always creates a stir of wonderment for viewers.

Because the sun is always active, no two eclipses are the same. Due to magnetic storms and high-energy particles constantly spewed out by our local star, each total solar eclipse has its own distinct personality.

The corona looks different each time.

As a first precaution, observers should never look directly at the sun with their eyes but don a pair of approved eclipse glasses or special filters (the same goes for attempting to photograph the event). Looking at the sun with unprotected vision can be especially harmful and cause eye damage.

During the moment of totality, however, direct visual observation of the sun can be made without any physical harm.

There are a number of interesting effects associated with solar eclipses.

From a high vantage point looking down, it is possible to see the moon’s shadow approach the observer from west to east.

The effect on animals and insects can also be noted. Birds will go to roost during a total solar eclipse while crickets will begin chirping when light levels noticeably decline.

Eclipses come in cycles. The next total solar eclipse in the continental United States will take place in 2024. The prime observing area for that event will be in a swath from Texas through the Midwest into New England.