Have you ever felt like a ball tossed around by the whims of fate, then found yourself wishing for resiliency to bounce you back into the steady rhythms of life? Longtime El Cajon resident Guy Sarver would have two answers for you, if you have encountered these unsettling sensations.

Have you ever felt like a ball tossed around by the whims of fate, then found yourself wishing for resiliency to bounce you back into the steady rhythms of life? Longtime El Cajon resident Guy Sarver would have two answers for you, if you have encountered these unsettling sensations.

On the practical, mechanical level, Sarver built a baseball catching machine that will do just that—throw back in about four seconds a ball that has been thrown at it. And on the personal, metaphorical level, Sarver has come back himself, after repeatedly being thrown off course by injury, financial hardship and illness.

Sarver spent almost all of his life in El Cajon, until a move to Encinitas this past month. He attended local schools Madison Elementary, Montgomery Junior High, Granite Hills and Grossmont College, where he was a college baseball pitcher. Sarver’s first big setback arrived with a mid-1980s motorcycle accident. His injuries included a damaged rotator cuff that ended his prospects as a professional baseball player. After overcoming his disappointment, he became a baseball scout for the Chicago Cubs in 1991 and declares that he “never looked back.” He also provided professional pitching lessons to young would-be professional athletes.

After too many crouching sessions as a catcher taking the measure of young pitchers, Sarver had the brainstorm for design of a catching machine that would return baseballs to pitchers, for an uninterrupted flow of throwing.

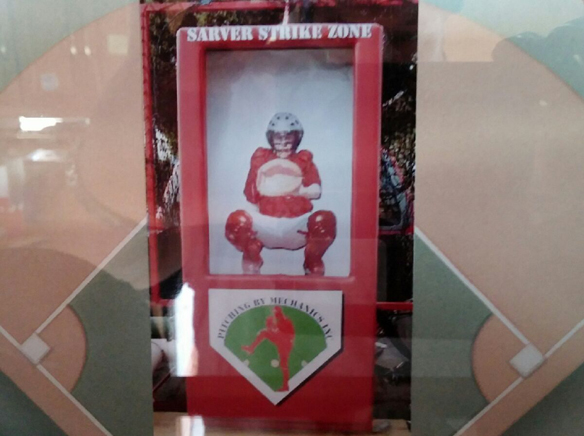

The result was the Sarver Strike Zone.

Relying on his training in electrical engineering and his understanding of the dynamics of pitching, he built a model of his machine. He incorporated his newfound enterprise on April 8, 2009, as Pitching by Mechanics, Inc., and set out to market his invention.

The outlook was bright, he thought. Nothing like his catching machine had ever been seen. He applied for a patent for his “receive-and-return apparatus.” The closest product came out in the 1970s and was only a net assembly that lost more baseballs than it returned. Other inventors had abandoned their catch-and-return devices because production costs were higher than projected sales, and his design seemed more affordable, portable and effective. So, Saver hit the road in his RV.

But then, he hit the wall financially. He drove 13,000 miles, on a route planned around baseball destinations from the Little League World Series to Cooperstown. By summertime 2009, neither his invention nor his road trip was paying off. He was broke, and almost broken. Depressed and homeless, Sarver entered the East County Transitional Living Center in 2010, for a three-year stay. Gradually, he regained confidence in himself and in his invention.

And he has come back for another tryout during the past six months. He’s bettered the design of the Sarver Strike Zone, for increased capabilities, including options for baseball return simulating grounders, fly balls and line drives, for practice in fielding skills. A remote control option is available for coaches to program training sessions for duration and difficulty level from afar, as well as a user interface for assessing overall performance and skills improvement from a practice session.

Longtime professional players have taken note. Mike Sweeney is impressed. “I wish this were available 20 years ago,” he said.

John D’Acquisto said, “This is a great machine that works. I use it.”

A diagnosis of lung cancer late last year did not stop Sarver. Neither did radiation sickness, and the radiation treatment appears to have been successful in knocking out the cancer. Sarver auditioned in February for an appearance on “Shark Tank,” the reality television series about investment. He is in contract negotiations with three major sporting goods retailers. He’s talking with a well-known restaurant chain about sponsorship. His machine went to manufacture at the end of March. He says he is “the sole guy right now” in his business, but he envisions hiring employees in about a month because he will have to. He was even able to buy back his old RV, and some of his prized baseball mementoes were still inside and intact.

Sarver has just reached the half-century mark of life, turning reflective over his own trajectory. He attributes his comeback to reliance on restored trust in God.

“I thank God for where I am, I give all glory to God, for bringing me through everything I’ve been through the past five years,” he said.

He coaches youngsters at baseball camps five to six times each week, and he wants to ensure that his machine is affordable for anyone’s pocketbook. Still, he worries about young players and how they are being taught to play the game.

“Very few pitching coaches know what they’re doing. Even in the major leagues, only a handful knows how to teach pitching,” he said.

Sarver’s concern is that inferior training will “wreck kids’ arms,” destroying promising pitchers before they have a chance to mature into the baseball craft’s physical mechanics. He believes his machine will improve training for pitchers by its consistency in ball reception and delivery, encouraging the correct mechanics of pitching.

“It’s why I named the company as I did,” he said. “My machine is in a league of its own.”

Guy Sarver is too.