The East County Homeless Task Force held a bi-monthly meeting Nov. 13 featuring Community Housing Works’ Senior Vice President of Housing and Real Estate Development Mary-Jane Jagodzinski and Project Manager Jana Zawadzki who explained some of the challenges in bringing affordable housing to San Diego county based on experiences in East County, National City and North County.

“We believe opportunity begins with a stable home. We serve more than 10,000 families, seniors and disabled persons in resident-centered communities that are sustainable with measurable impact, have onsite programs for residents,” Jagodzinski said.

Some of the items she listed as integral to a sense of community were deceptively simple, such as including a laundry room on site, ideally, she said, near a play structure where families can get to know each other and a main hub with a bulletin board for residents to share neighborhood information.

Others were about subtly weaving healthy lifestyle choices into communities, like building what she calls “Cinderella staircases” that tempt residents to walk up the stairs instead of taking the elevator.

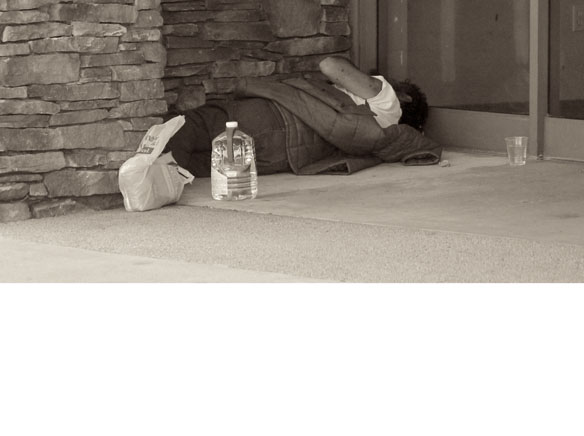

“What does affordable housing look like? We go out to the communities and Housing and Urban Development, over the years, did us all a disservice by building these things that look like projects. How do we fit in the neighborhood and afford it with the sources we have and not stick out?” Jagodzinski asked.

There is often some amount of pushback, she said, which is embedded in practical-sounding concerns that amount to rejecting the idea of affordable housing. She and other staffers have even been guided by marketing, she said, to replace the word ‘housing’ with ‘community’ to reduce the stigma associated with affordable housing.

“Very seldom does anyone come out and say “I don’t want those people in my neighborhood’ so they say things like ‘too much traffic, bringing in too many people to the community, it’s going to bring in crime, doesn’t fit the character of neighborhood, overburden schools, diminishing home values, not enough parking’.

She has also heard that building anything too nice is pointless because it will be destroyed. In answer, she often refers people to National City’s Paradise Creek development that “started out extremely problematic with difficult soils” and is now touted by city leaders as a success story.

“The park there was largely paid for out of our project and it is pristine. If you build something beautiful for people, they are proud of it and they take care of it,” Jagodzinski said.

Paradise Creek was deliberately located a short walk away from trolley lines, answering what one meeting attendee, Community Outreach Volunteer Erica Shepherd said in a follow up phone call are the two biggest challenges she encounters while trying to help unsheltered East County residents find permanent housing.

“Housing and transportation are the two biggest things I come across as a barrier. The properties shown in National City looked good but my biggest concern here in East County is location. It’s hard to find property and also have proximity to the bus or trolley. People need to be able to access things like going to the doctor or getting services,” Shepherd said.

She also said she believes it is important to survey residents in a neighborhood to assess their needs because “the people talking is what makes it work in the long run”.

During the meeting, Zawadzki said it is extremely important to engage the community where housing might be built. After receiving pushback in one potential neighborhood, she enlisted the help of a resident who happened to grow up in a Community Housing Works development. The lady was able to personally speak to her neighbors in a town hall style meeting on how the support she received directly fed into her adult personal and professional success.

Meanwhile, Jagodzinski, who works “with the bricks and sticks” said her biggest challenge is securing funding for affordable communities.

“Mortgages are based on property income. Our upbringing costs are the same as any other building but our rents are much lower— for the same build price we have a smaller mortgage and the gap is made up by city and state funding. So, where does the equity come from? Tax credits are very competitive and often a bank like Union Bank comes in as an owner for 15 years and they get tax credits in exchange for a whole lot of equity,” Jagodzinski said.

Additionally, she said, they often need city and sometimes state funding.

One creative solution the agency employed to success in North county was in building a facility with ten apartments for transitional youth who were aging out of foster care: the building is located in Vista but the city of Carlsbad contributed part of the Community Block Development Grant funding to meet the regional need.

“Recently, I met with the city of Santee and made that suggestion as well: perhaps one city might have money, one might have land and if they consolidated their efforts… Being able to build these communities is all about the gap finances,” Jagodzinski said.

Sometimes, she elaborated, one pot of money can only be accessed with a portion of funding already in place and that seed money, even if it is a small amount, can pull in a multiplier of funding from state funding.

Occasionally, she said they will purchase and redevelop existing properties, such as Maplewood, a 79-apartment community located in Lakeside that “was a really substantial renovation” and, like other developments, includes requirements like “how far are you from a bus, how frequently does it run, is it near a pharmacy, a grocery store,” Jagodzinski said.

Zawadzki connects community health with physical health and describes the recent introduction of a 12-month long diabetes prevention program as well as a leadership academy so residents improve their life while benefiting from their surroundings.

It’s important, Zawadzki said, to recognize “affordable homes are not ‘those people’ and anything that helps support that funding is important because we’re part of the fabric of the county.”