The sanctuary

The sanctuary

Plumes of dust chaotically take over the bumpy dirt road as the scratched up ’91 Ford Ranger, the color of a smashed toad and with pealing off black vinyl on the inside, hiccups loudly as it makes its way on the Diary Road in the El Monte Valley in Lakeside, CA. Parking under an oak tree buzzing with song-birds thrills, we make our way on foot toward the East, crossing over hills blanketed in buckwheat, mule fat and sage, looking down the sand pits left un-restored for the past twenty years. The San Diego River bottom is a luscious and pristine wildlife habitat welcoming all kinds of creatures under the shade of the tamarisk, cotton willows and oak trees. Here and there, sycamore trees generously offer room for nesting to red tails, Cooper’s hawks and peregrine falcons.

One wrong step and you can feel the burn of a diamondback bite, which is one of the three rattlesnakes species that live in the area along with the Southern Pacific and the speckled. There are many roadrunners around, so the nature balances itself.

El Monte Valley is also home for several non-venomous snakes, such as the gopher, King, coach whip, and rosy boa.

The urban development is non-discriminatory with its victims. We find scorpions lurking on the ground (I count seven so far) and it takes a trained eye to spot them, as they are the treacherous color of the dust. A Blue-tail skink lizard plays dead on the trail as we approach a singing silvery cotton wood tree. It doesn’t really sing, but it sings to me.

Up above, the chatter of several turkey buzzards turns deafening as a kestrel makes its way toward a tall oak tree and a family of three golden eagles lands as-a-matter-of-fact on the SDG&E tower uphill. This is considered fierce competition. We can see the eagles through the 300mm Canon lens and hear their unmistakable shrill telling eagle stories to each other. Sometimes, a peregrine falcon bored with the menu available at El Capitan Reservoir Lake behind the dam, surveys the dove weeds meadows for a juicy pigeon. There are so many hawks around, the red tail, sharp-shinned, Cooper’s, the Northern Harrier, then there is the rarely seen black hawk. The white-tailed kites like to land on the bamboo fields at the abandoned Taiwan Farms near the orange trees where they can dive for rats. Usually, we spot prints left behind by bobcats and coyotes and on lucky days, mountain lions and grey foxes. Mostly horses though, as this is the backcountry of everything western.

In the morning, the sky gets plastered with songs and wings coming from quails, Northern Shrikes, swallows, kestrels and doves. At sunset, hundreds of bats escape from the rock quarry at El Cajon Mountain, flying in harsh strokes across the valley, preying on unsuspecting moths and other bugs. Over a year ago, when we were searching for the Arroyo toad at midnight, we found a baby Grey Horned Owl sitting on the road, then we spotted several nests in the surrounding trees. There are many other visiting birds from the Lake Jennings across the Flume Trail, such as ospreys and bald eagles we managed to document so many times.

The abundance of wildlife in the valley is crowned by the existence of several endangered species that are federally protected: the gnatcatcher, glossy snake, checkered butterfly, Least Bell’s Vireo and the California Red-legged frog. Little do they know these few rare creatures could save the whole valley from destruction one day.

Looking up ahead, El Cajon Mountain cradles the El Monte Valley, covered in glittery amber at sunset, radiating a rosy light due to the iron contained by the rocks. Hundreds of ranches and houses spill bellow, privileged witnesses of the natural wonders abounding in the valley and continuing a way of life that’s a couple hundred years old. This is the backcountry, the old Wild West some of us foreigners were fascinated with in the movies.

The place where the hand on the gun was way too fast for death to catch up with it and the rawness of the land got imprinted into people’s souls and lives, giving them a hard shell on the outside and a softer melody on the inside. The country where people do not wonder anymore which part is bonding and which part is a struggle with their horses and cows, where they eat what they hunt, usually deer and small game deep in the forests and thick chaparral up in them wild surrounding mountains. The country where people kick off their cowboy boots at the saloon on Sunday after the church closes its doors and the last Psalm of the day lost its echo. The East County of San Diego, one of the last near pristine lands full of real wild life and traditions.

Acorns homage for old sins

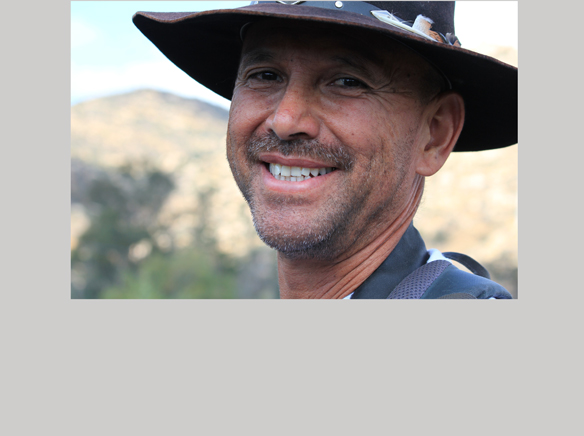

The man in front of me throws long shadows on the ground as he walks on this dusty trail in the valley and his black felt Crushable Stetson hat is darkening a bunch of California puppies cooling off in the wind. Billy Ortiz knows every inch of the El Monte Valley, down, up, above and beyond. He notices changes from one trip to another, the way wind blows, how some trees lost their branches, how the doves moved to another meadow – escapable nuances to a profane eye. Speaking of eyes, his are squinting slightly even when the light is not blinding, but stubbornly scanning the elusive horizon for blurry shapes of golden eagles, his soul’s twin bird.

It looks like his skin changes colors, from dark tan marked by deep crevices to a more transparent and soft shade, maybe because this is where he feels in his element, in this valley his heart calls it “home.” So, he takes the shape and the color of the place. Born and raised here, Ortiz calls himself the son of Lakeside. “When the day comes,” he says, “you can spread my ashes over the valley from the top of the El Cajon Mountain.”

The whole acorn reenactment idea is a ritual meant to honor our ancestors’ spirits that still live in the valley, because of something wrong Ortiz thinks he did many years ago at the Indian Village. The Native Kumeyaay lived here for thousands of years before the Spaniards conquered their land and there are many clues around telling about a prosperous and happy life. With a bag full of pealed acorns, we are heading up to the Indian Village where he knows how to find metates and some left-behind round, smooth rocks used for crushing.

He just asked for forgiveness and we think he received it, judging by the serenity of the moment. It is a spiritual experience, but mostly for him. Ortiz believes he was punished with Valley Fever for digging around these rocks back in 2009, when a friend told him he could do so. Back then, he did not know any better and ended covered in dust head to toe, breathing it all in, and with flu-like symptoms, plus pain on the left side of the chest few days later. After seven days of taking antibiotics, the symptoms got worst and he ended up at the emergency room. He then remembered how his friend got sick of Valley Fever at the same site.

One night while he was taken by high fever, he had a haunting dream of an old woman dressed in Kumeyaay clothing. “I could not see her face, but based on her whole demeanor, I could tell she was mad at me. I felt that in my heart, as if I did something that I shouldn’t have done and now I’ve got this woman upset at me. I think that was a spirit of a Native telling me to right the wrong I’ve done by digging on a sacred land.”

Now the doctors knew what the problem was. Six months of strong medicine and six more months of recovery made Ortiz one of the very few lucky ones who got out of this alive or healed. Most of the people who get infected by this fungal infection caused by coccidioides (Valley Fever) suffer their whole life or die. It is a very insidious and resistant fungus that settles in the lungs first and then adapt to the medication forming a hard shell for defense.

Ortiz is not the only one who got sick from Valley Fever in the El Monte Valley. He does know the real cause for his illness – the dust in the valley heavy with fungus in some areas. However, because of his very profound ties with the spirituality of the place, he thinks there is always another layer of a sacred meaning to our mundane existence.

Sand mining in the El Monte Valley

He tells the story about the Valley Fever to anybody who wants to listen, working hard to raise awareness about one of the many risks posed by a sand mining project proposed for the El Monte Valley and opposed by the majority of the people who live in East County.

In 1997, El Capitan Golf Course, LLC wanted to build a golf course in the El Monte Valley. They leased the land from Helix Water District and started to sand mine the first year, supposedly without a permit. Since then, the company never restored the huge holes left in the ground that desecrated the valley on both sides of the Diary Road. Helix Water District sued and they battled in court until reaching a settlement in 2014, allowing the golf course company to buy Helix’s property for $9 millions, with $1 million payable upfront. The sand miners are trying to get the permits before the deadline for the total amount is coming up in 2017.

Recently, this company changed its name into El Monte Nature Preserve, LLC (EMNP) and co-opted Michael Beck, a very well known environmentalist with an impressive background representing Endangered Habitats League. Beck’s role is to restore the land into a riparian habitat to attract a Tricolored Blackbird that doesn’t live in the area, after the digging is done in 15-30 years from now. The opposing voices to this project point out that Beck, as an environmentalist, should protect the environment, not to be a proponent to a sand mining project. Beck is also the Chairman of the San Diego County Planning Commission. Many people accuse him of conflict of interest and are requesting Supervisor Dianne Jacob to ask her appointee to resign.

The initial plan was to dig a 100-foot deep hole on about 256 acres to begin with, and then hope to expand the area, using hundreds of trucks every single day in and out of the construction site using the two-lane El Monte Rd, the only paved road out of the valley. That is a crater as deep as a 10-story high building and as large as 300-500 acres, which makes it twice as tall as Qualcomm stadium and as long as the Coronado Bridge.

The main argument pro-sand mining is that the El Monte Valley is a deserted area with no significant flora and fauna and it would be better off as a resurfaced aquifer and turned into a pond like it happened at Hanson Pond, another sand pit on the West end of the valley.

Impacts and concerns

The San Diego River aquifer in the valley is the third largest in the San Diego County and supplies water to East County. Removing the natural sand filter in the underground river to create a riparian habitat will affect the aquifer exposing it to resurfacing, contamination and evaporation. That would also leave the people on wells without water.

There is a very high risk of spreading Valley Fever way beyond Lakeside’s border by stirring up huge clouds of sand. This fungus is located in the valley, usually around Native Americans artifacts sites and it can be spread by wind. People do inquire about what is more important, the profit from sand mining or the public health?

El Monte Valley contains such lush vegetation and many endangered species that will be extinct and completely destroyed. Two roads, El Monte Rd. and Willow Rd., officially designated as scenic corridors, flank the valley on both sides. Residents fear that these roads won’t be scenic anymore without the scenic valley. These two roads connect the town of Lakeside to a very rich valley not only in historical artifacts, but also in biodiversity, and which constitutes the heart of this community.

Many local businesses are thriving in the valley and one is already a landmark: the Van Ommering dairy farm – a place visited for instructional purposes by thousands of kids every single year and one farm that becomes a very popular Pumpkin Patch destination during the holidays. Moreover, many horse-boarding facilities will lose their place and their customers won’t have access to any more trails in the valley.

The man with a black hat

“It’s a kind of fever that’s not always hot to the touch, but sometimes gives you chills,” Ortiz said, describing his Valley Fever symptoms. I look over the El Monte Valley from up the hill where we are now on a private trail and see it glowing in the sunset with soft shades of green and gold. Ortiz’s truck broke down and is breathing smoke from the overheated radiator. This valley seems to hold more than the fungus causing the Valley Fever. Everyone I spoke with seems love struck with this place, as if there is a devouring spirit lurking in the underground river that eats souls for breakfast and cannot survive without making people fall in love at first sight.

There is also a type of fever raging from greed, born in hungry bellies craving for money and power, the fever that fuels so many to conquer this valley and turn it into a dump after sucking about $2 billion worth of sand out of it. We start down the hill in this wonder Ranger that is now fueled by a miracle and I think back to the stories Billy told me about how he started his fight to save his valley. This valley, everybody’s valley. Well, Ortiz’s valley for now.

We have to stop the truck and get out for now, as Ortiz has one of his many panic attacks that leaves him the shell of the man he really is when healthy. Breathing techniques, visualizations, stupid jokes to make him laugh, talking about stuff to distract his attention – sometimes nothing works. Jittery and spent, he sits on the ground, head between his hands, not knowing when is his state of mind is going to end. In an out of the ER more times than he cares to mention, Ortiz is living on the edge most of the time, riding the life with an insatiable hunger and enthusiasm in between his health crisis. Weakened and with a knot still turning his chest inside out, he slowly makes his way out of the darkness, standing up, reaching for hope, grabbing at his core strength and finding it for the day, until another crisis stops by and punches him to the ground again.

Ortiz and Beck seem to live in two opposing world while looking at the same thing in the same time and seeing completely different realities and seeking opposing opportunities. One seems to be the man of a future built on cement and closed up spaces, while the other is still looking for the past under breathing trees and in the eyes of crying baby eagles.

Two men locked in a battle that’s not between equals and to win the heart of an elusive nymph that doesn’t belong to either one of them. I am talking about the valley. The same valley that’s consuming people’s lives on such level that some may lose their career over it as the story keeps blowing up in high offices lately and some may become filthy rich, while others may succeed in saving the valley, like Ortiz here, the solitaire man with the black hat who already lost his sleep, his peace of mind and health over it.

Ortiz tells me he will never stop doing everything in his power to save the valley from destruction. He started exploring the valley and the surrounding mountains back in 2009 when he first found out about the sand mining project and about a group of locals who started organizing themselves in order to oppose the project. He was and still is the one who travels the valley on foot and documents all the living creatures through his video and photography. The community rallies around him. He holds the symbolic flag of this consuming fight. His wonder Ranger joined the movement too, plastered with a “Stop the Sand Mine!” sign on the back window.

He is posting all of his adventures on social media and is growing a huge group of followers who are living vicariously through his lenses and stories. Very well respected in town and loved by the community, Ortiz has many accomplishments under his belt as a member of the Lakeside Historical Society and a volunteer for many other noble causes. He seems to always be on call for everything that’s going on around town, being that a pair of dogs lost on the freeway or the old historical sign that needs to be dismantled and replaced. Everybody reaches out to him with questions about everything and anything or with requests for help and assistance. Last time I saw him doing something very Billy-like was to give out his jacket to another ER patient on a cold and rainy day. He went home shivering in a t-shirt.

The black hat he is wearing now is a new one and already looks ancient, tattered like tumbleweed rolling too fast in the ravines. He wants to donate his old one to the local Historical Society as being the one thing that makes him recognizable by most everybody, everywhere he goes. His black felt hat and his 300mm Canon lens hanging around his neck. He perceives himself as one of the last cowboys, but I do not see him reassembling such raw and sharp force. He wears hiking boots and a hiking backpack where he usually stores bananas, peaches, peanuts and some Cliff bars and that’s not cowboy food by any stretch. The hat alone won’t do either. What else? Even his guitars are electric. And he drinks decaf and writes poetry.

As much as I am able to understand this man and his story, the main reason people trust Ortiz, look up to him and are able to relate to him so well is because he is on a healing path himself and his personal journey opens him up to resonate so profoundly with every other wounded being or place. El Monte Valley is burning with all kinds of fever and Billy Ortiz may be the one man able to save it for all, once he finds the right healing potion for his own wounds.

“Where do we go from here, Ortiz?” I ask. “Let’s go north,” he said, while his double-jointed finger joyfully and crookedly points to the West.

I regard something truly

I regard something truly interesting about your web blog so I saved to my bookmarks. http://coloredconventions.org/mediawiki/index.php/The_Most_Useful_Supplement_Along_The_Market