By Hector Valtierra

SPECIAL TO THE EAST COUNTY CALIFORNIAN

By Hector Valtierra

SPECIAL TO THE EAST COUNTY CALIFORNIAN

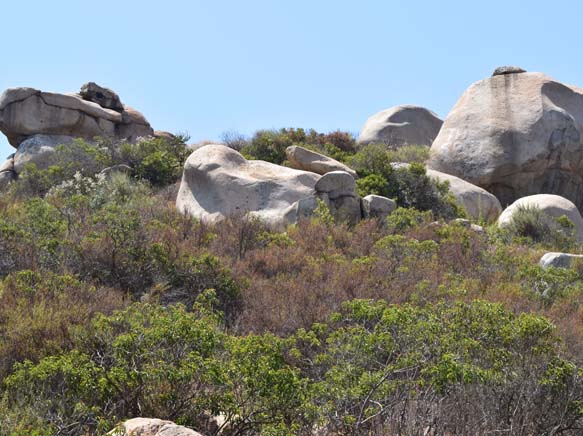

Earlier this month the El Cajon-based Earth Discovery Institute, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and a handful of community members, including students from Cuyamaca College gathered in the early morning at the San Diego National Wildlife Refuge south of Rancho San Diego to clean graffiti from some of the giant boulders lining the north-facing side of the canyon., In just a few moments, taggers, or the people who use spray-paint to mark up the walls, billboards, the sides of semi-trucks can, or the undersides of bridges were able to deface this natural setting. It is becoming increasingly common and takes much time to restore the area to the way it was.

Graffiti, or tagging, the natural environment has become more common recently. The most recent incident was in early May and involved a high school student asking another student out to prom by spray painting on the side of an Ada County, Idaho cliff on Bureau of Land Management land. The words, “DESTINY, PROM?” were painted in pink and blue on the side of the cliff wall with the tagger probably using climbing equipment or a ladder to get it to the heights that the letters were written. In 2014, 21-year old Casey Nocket, under her pen name, or tagger handle, “Creepytings,” painted her artwork on the sides of eight to ten National Park cliffs and boulders in four states. What made her case particularly notorious was that she posted pictures of her handiwork on Instagram. Hitting closer to home is first-time graffiti found on Barker Dam in Joshua Tree National Park. As the park hosted its largest amount of visitors in a year in 2014, some 1.6 million visitors, along with these crowds came vandalism.

As many parks are understaffed, it is increasingly difficult to monitor natural sites. As such, graffiti can be left for weeks until a member of the public contacts the appropriate officials. Such was the case at the San Diego National Wildlife Refuge. Members of the USFW service, EDI and myself performed a trial run for cleaning the graffiti on boulders in Steel Canyon in mid-April. Using wire brushes, some four different brands of solvent, rags, and carried-up-the-canyon water, we discovered which solvent worked best. As the amount of graffiti outnumbered our supplies, we set another date to return in May with more person-power and more solvent. That is when a handful of community members and students volunteered to assist. As the budget of the nation’s parks have been reduced concurrently with the number of visitors increasing, it becomes increasingly difficult to find the person-power to clean up the graffiti. That’s where organizations like EDI and biology professors (who offer students extra-credit for cleaning up graffiti or assisting with river or beach cleanups) step in.

To be certain, man has been writing on natural canvasses like caves, boulders, and cliffs for millennia. Think Lascaux in France or petroglyphs in our own county. But graffiti in a natural setting is different; there is no benefit to the community. At the time these early scribing’s were done, there were very few people inhabiting the natural environment. Now the situation is reversed. There are over three million people in San Diego County and the USFW, EDI, and other federal and state organizations are trying to preserve what little natural space we have left. In several places around the County, cookie-cutter housing complex and new roads invade the chaparral and its original residents. Although graffiti may accentuate the landscape of an inner-city, think Logan Heights under Coronado Bridge (or pretty much under any bridge for that matter), it is an eyesore to say the least in wildlife refuge. When I first noticed the graffiti in Steele Canyon, I e-mailed Jill Terp at the USFW service and was relieved to receive an e-mail later that evening stating she had been at the site earlier in the day to figure how best to tackle the problem of cleanup. I volunteered for service, along with Cathy Chadwick of the EDI, and we set out one day in April to clean up.

Visiting nature is, as seen in Joshua Tree National Park and other national, state, county, and city parks, is becoming more essential to city-dwellers. As the San Diego Wildlife Refuge is within drivable range, it is a common spot for hikers, mountain-bikers, photographers, birders, and wildlife watchers in general. I’ve seen a roadrunner there, many species of lizards, butterflies, and birds as well as evidence of coyotes. It is a thriving ecosystem. Families come here as well as people taking their dog out for a jog. Sweetwater River runs through Steele canyon and it is a great place to get-away from the asphalt and concrete grind and roads of metal traffic of the city. The Wildlife Refuge presents a time where people come to unplug from the circuitry of a routine life. And so, early morning before the heat was turned-up, dedicated USFW, EDI, and community members met to erase, with a little elbow grease and the effort of carrying cleaning equipment and water up the canyon side, the increasing sign of the times.

Hector Valtierra is an adjunct professor of general biology and microbiology at the Grossmont/Cuyamaca and Southwestern College Districts.