History speaks for itself. On Jan. 18, 1958, Willie O’Ree — a 22-year-old forward from Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada — became the first black man to play in the National Hockey League when he suited up for the Boston Bruins in a game against the Montreal Canadiens at the Montreal Forum.

The game of hockey has certainly changed over the 60 years since O’Ree made his history-making debut. O’Ree — dubbed the “Jackie Robinson of hockey” — has helped forward that change.

History speaks for itself. On Jan. 18, 1958, Willie O’Ree — a 22-year-old forward from Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada — became the first black man to play in the National Hockey League when he suited up for the Boston Bruins in a game against the Montreal Canadiens at the Montreal Forum.

The game of hockey has certainly changed over the 60 years since O’Ree made his history-making debut. O’Ree — dubbed the “Jackie Robinson of hockey” — has helped forward that change.

The NHL consisted of just six teams — the Original Six — when O’Ree, a speedy winger, first touched the ice with his blades. NHL membership now stands at 31 teams with the addition of the Vegas Golden Knights this season and is as diverse as ever from a player standpoint.

Thirty countries can claim players in the NHL. There are 24 black players in the league this season.

But there was a time when hockey wasn’t so diverse — even when other major sports in North American had already broken the so-called color barrier.

Since O’Ree’s barrier-shattering debut, 85 other blacks have played in the NHL.

P.K. Subban, a defenseman for the 2017 Stanley Cup finalist Nashville Predators and one of the league’s most prominent black players, called O’Ree a role model to any player from a different country or minority background.

O’Ree was the pioneer, and his is a legacy is one to be celebrated.

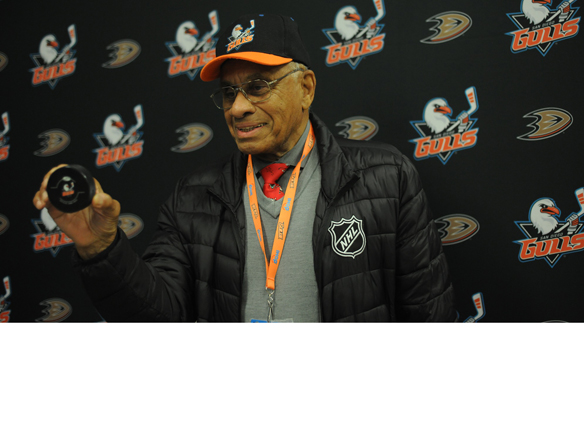

O’Ree, a long time resident of La Mesa who is now 82, provided the showpiece for the San Diego Gulls’ inaugural Diversity Night on Jan. 20 when the American Hockey League club hosted the San Jose Barracuda.

The Gulls, the top developmental affiliate of the NHL’s Anaheim Ducks, celebrated Diversity Night to raise awareness of diverse groups in hockey and drive positive social change and foster more inclusive communities within the sport.

The Gulls recognized diverse groups throughout the game, including You Can Play, an initiative that works to ensure safety and inclusion for all who participate in sports, including LGBT athletes, coaches and fans; the San Diego Sled Hockey Team that is comprised for disabled and able-bodied athletes ages 14 and older, including active duty military and veterans; and the San Diego Chill, a non-profit organization dedicated to helping children with developmental disabilities play ice hockey.

The Gulls wore special diversity-themed warm-up jerseys that were later put up for auction for charity.

O’Ree, otherwise known as Mr. Hockey in San Diego, dropped the ceremonial puck.

It was the latest of many celebrations marking O’Ree’s 60th anniversary of breaking pro hockey’s color barrier.

He received a standing ovation, starting from the benches of the Bruins and Canadiens, when he walked out to center ice at TD Garden on Jan. 17 to drop the ceremonial puck one day shy of 60 years after becoming the first black player in the NHL.

NHL Commissioner Gary Bettman was on hand for the ceremony; the city of Boston proclaimed Jan. 18, 2018, as Willie O’Ree Day.

On Nov. 3, O’Ree was in Springfield, Mass., for ceremonies devoted to O’Ree breaking the color barrier in the AHL as well. It was on Oct. 12, 1957, that O’Ree became the first black player to skate in the AHL when he took the ice for the Springfield Indians in a game against the Buffalo Bison.

Three months later, O’Ree made his NHL debut with the Bruins.

During his visit he was inducted into the Springfield Hockey Hall of Fame.

“It’s wonderful,” O’Ree remarked about the buzz marking his history-making feat. “I was thrilled when I was in Boston. It took me back to when I first came to the Bruins in their training camp in 1957. I kind of fell in love with the team and the entire Bruin organization.”

What does he remember about the history-making event?

At the time, O’Ree was playing for the Bruins’ minor league team, the Quebec Aces, in the Quebec Hockey League.

“The Bruins contacted the Quebec Aces, the team that I was playing for, and said they wanted me to meet the Bruins in Montreal to play two games – Saturday night in Montreal and Sunday in Boston,” O’Ree recalled.

“When I arrived in Montreal, coach Milt Schmidt sat me down and Lynn Patrick, the general manager, sat me down and said ‘Willie, we brought you up because we think you can add a spark to our club. You’re no stranger here to the Montreal fans and just play your game and have a good time and basically that’s what I did.”

O’Ree said Schmidt told him not to be concerned about “anything else.”

In fact, as far as O’Ree was concerned, he was just busy doing his job – being a professional hockey player.

It was only after reading newspapers the next day that he realized the significance of his first NHL call-up.

“It was the next morning that I found out that I did break the color barrier and opened doors for not only black players but players of color that are now playing in the NHL,” he said.

O’Ree’s NHL career lasted just 45 games over parts of two seasons and there would not be another black player in the NHL until the Washington Capitals drafted fellow Canadian Mike Marson in 1974.

But O’Ree, who drew praise for the manner in which he conducted himself in the face of racial prejudice as the only black player in the NHL in the 1960s, would cement his legacy during a long and productive career in the Western Hockey League from 1961 to 1974 as a member first of the Los Angeles Blades (1961-67) and then the original San Diego Gulls (1967-74).

O’Ree won two scoring titles in the WHL and scored 30 or more goals in five seasons.

Blades head coach Alf Pike may have made the biggest contribution to O’Ree’s career when he shifted O’Ree –- who had lost vision in his right eye due to a hockey injury during his junior hockey days — from left wing to right wing.

O’Ree’s offensive production jumped immediately — from 17 goals in 1963-64 to 38 goals in 1964-65 — to become one of the WHL’s most exciting players and prolific scorers.

Fans of the already wildly popular Gulls immediately fell in love with the speedy winger whose flashy full-speed rushes towards an opponent’s net drew excited shouts and cheers from crowds. O’Ree was a major reason the fledgling WHL franchise routinely saw home crowds soar past the 10,000 mark, the highest in North American minor hockey.

The WHL ceased operations following the 1973-74 season, but O’Ree came out of retirement to play one season with the San Diego Hawks in the Pacific Hockey League in 1978-79. At 43, he still proved he could contribute by recording 21 goals and 46 points in 53 games. He also logged 37 minutes in the penalty box.

O’Ree remains tied to the game he began playing at age 5 in his native Canada.

He now serves as the NHL’s director of youth development, works with children to expand opportunities and preaches a message of inclusion in hockey.

“I’ve had about three titles since I came to the NHL,” O’Ree explained. “When I retired from hockey here in San Diego, I wanted to give back to the sport and give back to the community what hockey had given me for the 21 years I was able to play professional.

“When the NHL came calling in 1996 I was very happy. Now that I’ve been with the program for 20 years — the Hockey is for Everyone program — I just feel very pleased about having the opportunity to reach out and touch boys and girls to help set goals for themselves and help them play another sport where they haven’t had the opportunity to play before.”

O’Ree has been one of the most well known ambassadors for the league’s Hockey is for Everyone initiative since 1998. The initiative uses the game of hockey – and the NHL’s global influence — to drive positive social change and foster more inclusive communities.

In his own words, when opportunity presents itself, the game grows.

“We have approximately 32 programs in the hockey initiative program,” O’Ree said. “The first thing I say is for these boys and girls to stay in school and get an education. Education is the key. You can’t go anywhere in the world these days without an education.

“As far as setting goals for yourself, you need to set goals for yourself. You need to work toward your goals and believe in yourself and feel good about yourself and like yourself. I’ve been doing this for 20 years and if I didn’t think the program worked I wouldn’t have stayed with it for 20 years. So just believe in yourself. If you think you can, you can. If you can’t, you’re right.”

I want forgathering useful

I want forgathering useful information, this post has got me even more info! http://wikitransporte.tk/index.php?title=A_Health_Nutrition_Guide_On_As_Well_As_Weight_Loss_For_Good_General_Health

I want forgathering useful

I want forgathering useful information, this post has got me even more info! http://wikitransporte.tk/index.php?title=A_Health_Nutrition_Guide_On_As_Well_As_Weight_Loss_For_Good_General_Health