The Marine Corps veteran who fought in Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) described his anger at the enemy, how “they were able to get me” with a mortar round. “I could take it face-to-face,” he explained. But being hit by a mortar round “wasn’t fighting man-to-man, “he said.

The Marine Corps veteran who fought in Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) described his anger at the enemy, how “they were able to get me” with a mortar round. “I could take it face-to-face,” he explained. But being hit by a mortar round “wasn’t fighting man-to-man, “he said.

Sitting down with a fellow Marine to learn his story is always a great way to share some comradery. Doing so on a sunny Saturday afternoon with El Cajon resident and Marine Corps veteran Robert Hernandez, recently named the Military Order of the Purple Heart California Department Patriot of the Year, was a privilege.

Originally from Dallas, Texas, Hernandez joined the Marine Corps in 2001. When asked why the Marine Corps, he spoke of always wanting to join the military and being impressed by the Marine recruiters at the Texas State Fair, saying, “they held themselves to a higher standard.” His parents were not exactly thrilled by his joining the Marine Corps, but since there was no war at the time, figured he would complete his enlistment safely and return home to join in his father’s business. As Hernandez tells it, his mother thought he “would play Marine and come home.” That was not to be.

He reported to the Marine Corps Recruit Depot San Diego and completed boot camp on 7 September 2001, just days before to the terrorist attacks on 9-1-1.

Assigned the Military Occupational Specialty (MOS) of 0311 – Rifleman – he attended follow on infantry training after boot camp and was subsequently assigned to Second Battalion, Fourth Marine Regiment – nicknamed the “Magnificent Bastards.” By the time his battalion shipped out to Iraq, it was 2004, Hernandez had been promoted, and he was serving as an infantry squad leader.

He spoke of the fight for Ramadi, Iraq, explaining his one infantry battalion was controlling a city of more than 500,000. Unlike Fallujah, where multiple battalions fought at about the same time, Ramadi was pretty much unknown to all but those who paid attention to such matters. He spoke of one particular day when the enemy launched multiple, coordinated attacks across the city.

“We lost 12 Marines and a Navy Corpsman. One of the worst days ever. That was a real gut check out there. Marines think we are invincible, we can conquer the world,” he said.

Later, as he related it, the Marines took the fight to the enemy and were successful, even going out into the city and using bull horns to entice the enemy to “come out and fight.”

A few months later on 20 August 2004, Hernandez was wounded during a mortar attack on their base, when a shell landed between the barriers designed to protect them and the doorway to their hooch (Marine Corps parlance for barracks/living quarters), sending shrapnel into the room and wounding three, including Hernandez. Ironically, the shell that wounded these three Marines hit a considerable time after a sustained barrage. When that barrage ended, Hernandez was in the process of getting his Marines up and at it to go out and hunt down those who had fired on their base when the single mortar round exploded.

Prior to being carried to the aid station, Hernandez handed off command of the squad to his first Fire Team Leader. Such is the way of Marines; the next Marine in line takes charge. At the aid station, it was determined he should be sent to another medical facility for further examination, so he was put on a truck with others. Enroute to the next facility, the convoy was hit by an IED. No one was injured and the trucks were still running, so they kept going. After further medical examination, Hernandez was then MEDEVAC’d by helicopter to a hospital. “Somewhere in all of this, they had already informed my parents I’d been wounded. They were freaking out, because they hadn’t heard from me yet,” he recounted. At the hospital, it was determined surgery on his ankle was needed or risk amputation. The operation was successful and after a week he was told they could either send him home or back to his unit. Without hesitation, he chose to return to his unit, even though on crutches, and stayed with them until the command returned to the States in September 2004.

A year of physical therapy and a reenlistment later, he was an instructor at the School of Infantry at Camp Pendleton, determined to use his combat experience to train new Marines, so they could fight and survive. During this period, he met and married his wife, a local San Diego gal. When that second enlistment came to an end, they decided he should accept his discharge so they could settle down in this area.

Looking back at his time in uniform, he described being “shocked” after reporting to boot camp, what with all the yelling and rushing from place to place, leading him to wonder what he had gotten himself into. The Marine Corps is tough, according to Hernandez.

“It can be brutal, but it will definitely let you know what you are made of. You will come out from your time in the Corps proud of what you have accomplished,” he continued. “You’ll come a better person overall.”

Addressing the toughness and nearly impossible challenges, he spoke of the camaraderie and Marines helping each other. For example, he recalled completing a particularly long, grueling training hump (Marine Corps parlance for a hike), then having to set in defensive positions, digging fighting holes after “humping” dozens of miles.

“Tired, cold, hungry, and thinking it cannot get any worse than this, only to have it start raining. Looking back on it, I smile, knowing if I can survive that, I can survive anything.”

After separating from the Marine Corps, Hernandez and his wife settled down, as he returned to civilian life, got a job, and started college. He graduated from San Diego State University, where he was a member of the Student Veterans Organization, earning a bachelor’s degree in Criminal Justice. According to Hernandez, “Applying myself to schoolwork after being out for a few years was hard and required discipline while balancing a full-time job.” He went on to describe earning his degree as, “One of my greatest accomplishments.” (He emphatically declared the birth of their son as the greatest achievement since leaving active duty.) He now works for the U. S. Attorney’s office, where he has been recognized for his expertise.

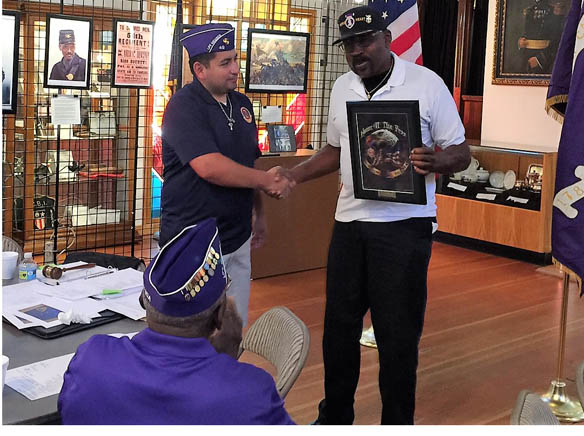

Hernandez joined the Military Order of the Purple Heart (MOPH) on the recommendation of a family friend back in Dallas, a Marine Corps Vietnam veteran and Purple Heart recipient, who encouraged him to join, citing the camaraderie he would find. The MOPH is a non-profit organization that advocates for veteran benefits. To be a member, each individual must be a Purple Heart recipient. For those unaware, the Purple Heart is only presented to an individual wounded, killed, or who dies of wounds caused by actions of the enemy. Therefore, as Hernandez puts it, every member of the Military Order of the Purple Heart “is a combat veteran who had shed blood for his country.” For his contributions to the Chapter and assisting veterans, MOPH Sunny Jones Chapter 49 nominated Hernandez for recognition as the Patriot of the Year. Some of his contributions include running bingo at the VA hospital; coordinating and organizing the leadership awards given to local ROTC and JROTC students; coordinating with other veteran organizations to put on events and help veterans in need, such as a recently discharged Army veteran needing assistance to pay his rent and provide some groceries for his family; and helping coordinate the upcoming Purple Heart Truck Run1 stop at the Veterans Museum in Balboa Park on 1 August.

Talking about life after active duty, Hernandez said, “The biggest thing I miss is the camaraderie. Even in the federal government, it seems like everyone is going their own way. In the military and the Marines especially, everyone is going the same way for the same mission.” In joining the MOPH, he sought the same camaraderie; to continue to experience that special bond between people who have served. According to Hernandez, “It is a common understanding of what you have gone through. Something civilians do not understand. Everyone working towards something greater than you.”

From his perspective, the Nation does not really understand veterans, seeming to lump them into one big group. “I get it, because if you never served, it’s really hard to understand what a veteran has gone through or what a veteran is,” he commented. Continuing, he related that most of the nation buys into stereotypes, thinking all veterans were always out there “shooting and everything, all the time. But it is not like it is in the movies. There were big lulls in the fighting.” Further, in his view, most people think of veterans as the proverbial old gray beards, not the younger generation.

Overall, he observed, “The nation is out of touch with veterans. Folks saying they support veterans is one thing, but not too many people really go out there doing what they can for veterans, particularly for the younger veterans. The average civilian does not really understand. They can throw money at it. They can donate. But all the veterans want is someone to talk to and ask them who they are as a person, not so much about combat.” And, sadly in his view, a lot of the younger veterans buy into the stereotype that vets are the old gray-haired guys sitting around the VFW bar drinking, and do not want to be grouped into that category. The younger guys “almost don’t want to be labeled yet” as veterans. They are still young, trying to work out their lives. Some want to totally disconnect from the military to get on with their lives. That is why they are not joining vets organizations in his opinion. But he and his fellow Marines with whom he served are not complacent, as share information on how to get in contact with one another. If someone is feeling down, they can reach out to one of their brothers. They do this on their own, continuing to take care of each other in the civilian world, just as they did in combat. He wishes more would do so, because one of his brother Marines committed suicide.

When asked what he got from his time on active duty, Hernandez explained the Marine Corps instilled in him leadership skills, which increased his self-confidence. Additionally, it taught him how to manage resources, be punctual, and manage time and events. Now he speaks with confidence, though professing to having been timid earlier in life. Speaking with that confident aura at the end of our discussion, he brought up a major concern related to Post Traumatic Stress. Too many service members are medically separated right after being wounded in his view. One day they are “in the fight” and almost the next day they are home among the civilian population, without that support structure of their comrades. There is no transition time for them. According to an example provided by Hernandez, a fellow Marine was wounded, losing an eye. After a week in a hospital overseas and another week at Bethesda Naval hospital, he was discharged to his hometown of Detroit. Away from fellow combat vets, in a civilian population who doesn’t understand what he has been through, and struggling. “One day they are ‘in country’ and the next day they are at home. They feel lost.” Maybe the absence of support during transitioning out of the military; the absence of that support from fellow combat veterans, maybe that is why some have issues with PTSD.

In his case, the additional years on active duty helped him get physically well and figure out what he was going to do. He knew he needed time to transition from combat to civilian life. Re-enlisting and remaining on active duty provided him that time. He described benefitting from the continued comradery and Marines helping Marines. He benefitted from that time and has effectively transitioned back into civilian life. A great family. Completing college. Successful job.

Yet, if you passed Marine Corps veteran Robert Hernandez on the street, you would be unaware of his history, service to our nation, sacrifice, accomplishments, and achievements. He is one of the heroes from the current generation of warriors who walk among us.

Nice job

Nice job