April is Genocide Awareness Month, and the Barona Band of Mission Indians is educating and advocating the history of Native Americans locally and nationwide through a series of blogs that are being included into the Barona Cultural Center and Museum’s historical archives.

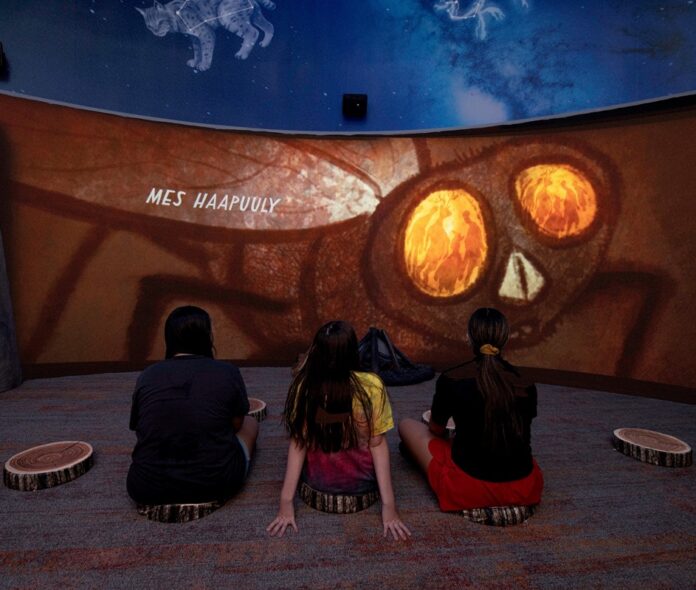

The Barona Museum was the first museum on an Indian reservation dedicated to the perpetuation and presentation of the local Kumeyaay-Diegueño Native culture, offering unique educational journeys for visitors of all ages. The museum’s collection represents thousands of years of history dating back as far as 10,000 years, demonstrating the artistry and skill of the hemisphere’s first inhabitants.

Museum Director and Curator Laurie Egan-Hedley said it was kind of a surprise for her in that she did not realize this was Genocide Awareness Month.

“I do not think that is widely known,” she said. “In talking with my superiors and colleagues here, we thought we should enter this arena and at least educate our audience about the genocide of the people here. We are planning four installments for a blog. One each week this month, and we have a display in our museum store with some recommended reading and more information and freebies that interested people can go home and learn more.”

Museum Committee Chairand Barona tribal member Steve Banegas is 61 years old, with four children and five grandchildren, and one great-grandchild. He has lived in Barona his entire life.

“I practice and hold very dear our ways, and what little we know about our spirituality, our beliefs, and our ceremonies,” he said. “They are starting to make a little bit of a comeback. This [conversation] should be for the entire country. The whole continent of the U.S. and others, the entire globe. When we talk about something as important and devastating as genocide, it is happening right now in other parts of the globe.”

Banegas said being Genocide Awareness month, there is little being said about it at local colleges and through the media.

“If you Google those colleges, they will talk about the Armenians, the Jewish, all the other examples of genocide. But every one of those institutions is on land that was once inhabited by a whole group of people that had a philosophy, had a religion, had a belief, and understood that they had a right to live and exist on that land. To make it clear, what I want to do with this awareness is number one, that it continues, and gives folks a view from the shore of what was once here. Not from the ship coming in. If you can look up a map, and you can Google it, what the original California nations looked like. It was huge. It was multiple people, multiple species, plentiful, rich for a very, very long time. It was actually a paradise. It was a gift from the Creator. The one responsible for putting us here. Some say 10,000, but there is evidence of 100,000 years of inhabitants here.”

Banegas said in 400 to 500 short years, the water is foul, the air is foul, the land is dying. He said recently with the Catholic Church and others rescinding some of their beliefs and admitting they have “made a mess of this” and put themselves in charge over Mother Earth, he said he always wondered who “we” is as they speak.

“We have been telling them for centuries that what you are doing is detrimental,” he said. “Aside from all that, the history, resources, and physical things, the most important to me is our spirituality. Our religious beliefs, our practices, have been oppressed and squashed for centuries now. We have become lost children in our own land now. We no longer recognize the importance of having places where you can worship…In the here and now, some bands, some nations, are operating gaming facilities. But with those gaming facilities we have to combat with the state of California. We have to pay money to the state. The state drags in billions of dollars off our endeavors. Yet, we get no services in return. We are responsible for our own health, our own housing, water, and education. All these things. I remind you. We are all on land once inhabited by original people that flourished for many, many centuries.”

Banegas said the origins of genocide should be taught and understood, even more so now.

“The way this country is going, we are so divided and against each other I think we are headed for some disasters if we do not change course soon,” he said. “That comes from understanding and appreciating one another.”

Barona Band of Mission Indians Councilman Joseph Yeats said his biggest drive is education.

“It is shocking the amount of people when we visit Sacramento, D.C., the amount of legislators that do not have a basic understanding of these histories. In California, Sacramento, these are people in their own backyard that they are representing. A large portion of what we do when we go to these places is education. Letting them know who we are. We are not all these big tribes you see in textbooks. There are thousands of us tribes scattered across the nation…How best to educate them and bring them up to speed on something that has been so lost or swept under the rug. As the chairman said here, it is a genocide that is still happening today. There is no point where we are not fighting for our existence.”

Yeats said even now, there are cases going before the Supreme Court that would “basically eradicate who we are, the original indigenous people.”

“For me it is finding a way to educate in this bite-sized 30-second TikTok world of ours that we are living in,” he said.

Several local government entities, including the city of Chula Vista, start their meeting with an acknowledgment of understanding that the ground they stand on is originally the land of the local tribes of the region.

“It feels like a token, and it feels very dismissive,” said Yeats. “We get a lot of land acknowledgements, but that is where it ends.”

Banegas said it is important for people to realize that they are still on this land.

“We still have a presence,” he said. “And we are still waiting for a treaty. This land is still ours. Some of us believe we are still part of it, but we are just temporarily removed. Until the United States comes with a true and just treaty that we can all agree to, this land has never been ceded or traded. But you must understand that you can only do those things when you put yourself above the law. The right to vote for Native Americans was in 1924. Prior to that you could not hold office, you could not vote, you did not have a say, you could not be a witness in a court of law. In order to have the rights and be stated as a citizen, you would have to leave the country, come back and apply for citizenship.”

On Tuesday, June 18, 2019, Gov. Gavin Newsom issued a formal apology to California’s Native American communities on behalf of the state for a history of repression and violence. The governor’s proclamation was part of a cultural moment in which Americans were increasingly grappling with the nation’s past sins.

“It’s called genocide. That’s what it was, a genocide. No other way to describe it. And that’s the way it needs to be described in the history books,” said the governor.

Banegas said that was 2019, and now it is 2023 and they are still asking when the changes can be made.

“Through education is what I believe is going to change things,” he said. “I hope. Once people know about it, they can turn from it.”

Banegas said when they are “acknowledged” by other governments, it is not enough.

“When they say we allow them to do this, or I think it is wonderful that they practice their own ways, that is putting us in history,” he said. “Our rights have been doled out over time slowly. It is almost like we are an afterthought. ‘Oh, they are still here? We better deal with this.’”

Banegas recommended a few books for people to read when it comes to genocide. “A Little Matter of Genocide,” by Ward Churchill. “An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846-1873,” by Benjamin Madley. “Murder State: California’s Native American Genocide, 1846-1873,” by Brendan C. Lindsay.

“Yet, I do not see any institution putting them in place and making them almost a requirement,” he said. “So, when we go to these meetings with these tokens, they cannot say once they were here but then miraculously, they went away. Bounties were put on the head of the original people in this part of the country. There was a systematic take the children and put them in institutions to teach them how to be home handmaids, plowshares, farmers…Never once was it to turn them into engineers, lawyers, or scholars. Those are all things genocide allows you to do. We are now just getting to the point where people are saying, ‘Hey, I want to acknowledge the people who were once here.’ Again, putting us like we no longer exist.”

Banegas said many institutions have violated the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act many times over with remains and artifacts under the guise of education, First Amendment rights, denying the right of every man, woman and child in this country the right to know.

“When you give yourself permission to do these things without being checked in 500 years, we are down, our language is struggling, our beliefs are struggling, our population is struggling. We are in constant fight for recognition with this country. It is like a disease,” he said, adding that he hopes to see more conversation about the past and ongoing genocide of the Native Americans during Genocide Awareness Month.

The Barona Cultural Center & Museum is open Thursday through Friday from noon to 5 p.m., and on Saturdays, 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., and is located at 1095 Barona Road, Lakeside, CA. Entrance to the museum is free.

For more information on its exhibits, classes and events, visit baronamuseum.com.

To follow the Museum’s April is Genocide Awareness Month blog visit www.baronamuseum.com/blog.