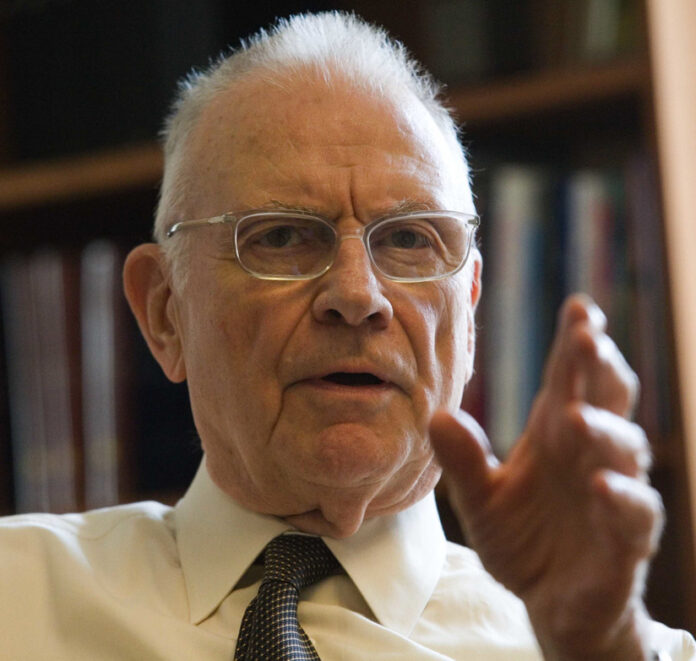

By Lee H. Hamilton

I don’t remember when it first occurred to me after arriving in Washington many years ago that at its heart, being a member of Congress meant never being entirely satisfied. And that this state of affairs is baked into our form of government. But despite moments of immense fulfillment, it remained a central tension throughout my time in office—as it has been for most legislators since the founding of the Republic.

Our founders were very clear about what they expected from the leaders chosen to represent the American people. “Government is instituted for the common good…and not for profit, honor or private interest of any one man, family or class of men,” John Adams wrote.

James Madison was just as direct, writing in The Federalist that the goal of a constitution like ours should be to put in office people “who possess most wisdom to discern, and most virtue to pursue the common good of the society.”

Politicians run for office for many reasons—ambition, ego, anger at the status quo, a broad but undefined desire to serve… And for some, that ideal—pursuing the common good—is front and center. This holds true for many voters, too. I’ll never forget once running into an elderly woman at the polls in Indiana and asking her if she’d voted. She responded by saying to me, “I vote for the candidate of my choice, but then I pray for the winner. I want him or her to work not just for the few, but for everyone.” That has always stuck with me as one of the healthiest attitudes toward politics I’ve ever heard expressed—and I’m confident plenty of voters feel the same way.

The problem, of course, is that there is no single definition of “the common good.” We live in a country that, instead, makes it possible for us to debate the question, to change our minds, to evolve, and to move forward when we can. But here’s the thing: The system is designed to make it hard to move forward unless enough people agree on an approach to command a majority.

In other words, they have to be able to find enough common ground with others—even if they don’t like everything involved in a given piece of legislation—that they can prevail democratically.

This is not easy to do, as any legislator will tell you—and as the entire country got a ringside seat for during the House speakership battle at the beginning of the year. For starters, of course, every member of Congress and legislator comes to the job with her or his own beliefs, attitudes, approaches, and red lines that can’t be crossed. Finding common ground among one’s own colleagues is hard enough.

And then there are the realities of the office: Constituents, party leaders, lobbyists, commentators—they all have their opinions, too. When I served in Congress, it was not unusual for me to have 15 appointments a day with people who wanted me to vote their way, often on some item involving the federal budget. Farmers came in to speak about farm programs, businesspeople to focus on business interests—their own and the economy in general—and religious or nonprofit leaders to lobby for support for their hard-pressed constituents. There was nothing sinister or malicious about any of this. It’s how the process of government works.

But it makes the task of finding enough common ground to move forward extremely challenging. So in the end, legislators are confronted with twin tasks: discerning and then pursuing the common good, and finding enough common ground with colleagues and the public at large to make progress possible.

Their job is to find a way to do both: to think in terms of what’s best for the country or their state or city, and then to weigh each of the considerations and pleadings they confront in that light. It’s tough work and no solution ever feels perfect, but if you’re committed to the job, there’s always another chance to edge closer to the ideal.

Hamilton was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives for 34 years.