When Wendy Esterly prepares to hike at Mission Trails Regional Park, she always make sure she has her DSLR camera with a 400-mm lens attached to it. “The camera is part of me. Without it, I feel lost,” she said.

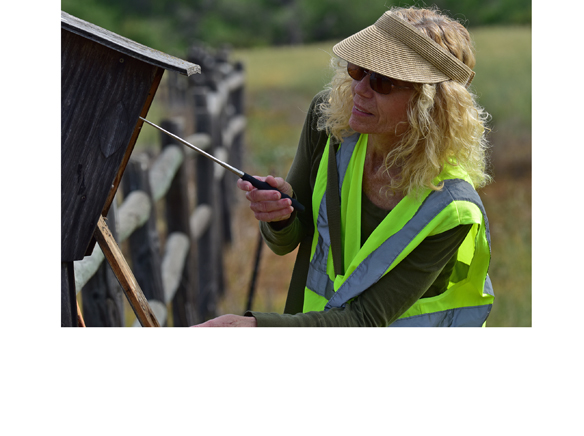

She puts into her backpack a Phillips screwdriver and a pair of work gloves. Then she checks to make sure she has her iPhone with her, and dons her bright green reflector vest and sun-protective hat. Now she is ready to go to the Oak Grove section of the park.

When Wendy Esterly prepares to hike at Mission Trails Regional Park, she always make sure she has her DSLR camera with a 400-mm lens attached to it. “The camera is part of me. Without it, I feel lost,” she said.

She puts into her backpack a Phillips screwdriver and a pair of work gloves. Then she checks to make sure she has her iPhone with her, and dons her bright green reflector vest and sun-protective hat. Now she is ready to go to the Oak Grove section of the park.

People glance at her curiously when she arrives at Oak Grove, for she steps off the trail into the more wooded sections.

“It’s why I wear the vest, which comes from the MTRP office,” she said. “If anyone stop and asks me what I’m doing, I explain I’m a volunteer.”

Esterly stops at a tree that has a nest box attached to it. She takes out her screwdriver, gently taps on the door.

“I knock to give the mother bird a chance to fly out before I check,” she said.

But she also knocks to give any other unexpected critters to leap out. A few years ago, a mouse leaped out at her when she was just starting to check a nest box. The box had had no activity the week before, so Esterly knocked on the side and proceeded to unscrew the door.

“Apparently the movement of the box woke up a little mouse inside and it leaped out through front opening lightning fast. It really startled me.

“After bypassing the box for about four weeks, I finally got the courage to open it. Sure enough, there was a mouse nest, but the mouse was gone. The box will forever be referred to as my mouse box,” she said.

Now, after using the screwdriver to unlock the nest, Esterly peers inside and sees a nest made of sticks.

“A Bewick Wren’s nest,” she said, notating it on her iPhone. “Bewick Wrens are very common around here.”

Upon hearing the call of another bird in a nearby tree, Esterly says it is a Warbler. She aims her camera up looking through the viewfinder and takes a photo.

As Volunteer Coordinator for the Nest Box Project at MTRP, Esterly knows birds almost as well as her own grown children. She first became interested in birds when she was just 6 years old and her had family adopted a pet Java Rice Bird.

“It was an active little bird and very interesting to watch. Also, my folks would identify birds that we would see at home and on trips,” she said.

When she heard about the Nest Box Monitor Project in 2004 while taking the trail guide training class, she knew she wanted to get involved. She began as a monitor and later became the project’s co-coordinator with Richard Griebe. He coordinates the management and manufacture of the nest boxes, and Esterly sends correspondence to all the monitors prior to and during nesting seasons and assigns monitors to the twelve different routes within the park. She also collects all of their information.

Over the years Esterly learned many interesting things about the birds that nest in the park, such as the House Wren. They are cavity-nesting birds that use many of the nest boxes. The male wren claims several potential nesting cavities and chases off the competitors. He fills the cavities or nest boxes with sticks and sings to attract a mate. He also inspects the nests of other cavity nesting birds and even those of other House Wrens.

The male wren is so competitive that he’ll sometimes pierce the eggs of the other species or even his own to take over the nesting site. Esterly was witness to this with a nest box on her route a few years ago.

There was a Bewick’s Wren’s nest with eggs in one of the boxes, she said. The hatch date was approaching. She saw that two had hatched and she could see cracks in the other three eggs.

Esterly did not want to disturb them anymore, so she returned the next day to check their progress. She saw a House Wren hanging on the opening of the box, singing.

“My approach made it fly, but I knew the bird was guilty of something. Sure enough, when I opened the box, all the young were gone. Although I knew it could happen, I didn’t expect to see it first-hand. The House Wren was guilty as charged,” Esterly said.

The other nest box monitors have had similar experiences.

“Not knowing what you are going to find when you open up the nest box is always fun especially when the nest you have been monitoring has new eggs,” said Petra Koellhoffer, who has monitored boxes for four years.

Koellhoffer remembers a time when she had checked on a box and saw that it was overrun with ants. The two remaining chicks were in distress, and one of them jumped out of the box and onto the ground.

“I picked up the baby and cuddled it in my hands. The chick immediately settled down and fell asleep. I closed the box and called Wendy,” Koellhoffer said.

So, to the rescue came Terry Esterly, Wendy’s husband. He discovered that one of the chicks had died and that was what the ants were after.

“After cleaning out the box of ants, I put my chick back in and it settled down and got comfortable, next to the other chick,” said Koellhoffer, adding that the chicks successfully fledged not too long after.

The Nest Box Project aims to educate and furnish information to the public on birds and bats within the park as well as to help expand the populations.

People interested in volunteering for the Nest Box Project should contact Ranger Heidi Gutknecht at hgutknecht@mtrp.org.